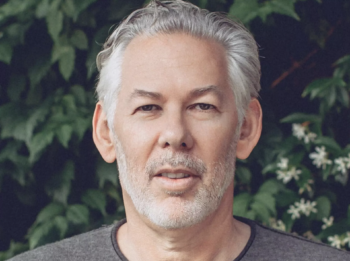

In the Information age, information may still be free, but snuggling is certainly not. Jackie Samuels, pictured above, is a social work graduate student charging $1 per minute for you to cuddle with her.

Yes, you read that right.

Known as The Snuggery, her Rochester, New York-based online business revolves around 45, 60, or 90-minute cuddle sessions, wholly un-erotic in nature, though her site claims that “arousal is perfectly normal and should not make anyone feel uncomfortable.” As I read through her FAQs and mission statement, I could not help but ask myself if Internet usage, so pervasive in our lives today, might take away from more social intimacy and drive entrepreneurs like Samuels to profit from our loneliness.

You’ve heard it all before: the average American spends eight hours a day in front of a screen, and 32.7 hours a week online. With nearly two billion Internet users worldwide, the increasingly prolonged time we spend away from face-to-face contact has undoubtably created a fundamental shift in how we view relationships and what defines human interaction.

According to a UK MySpace study of 16,000 social media users, the s0-called “Generation Y” is more comfortable confiding in “online” friends than with our physical counterparts. And the Internet jumped to respond to this human tendancy. Readers can now educate themselves with such wide-spread articles as Wikihow‘s “How to make friends online,” further amplifying the gap between traditional face-to-face time and what has become a new standard.

Despite mounting levels of virtual connectivity, the irony of it all is that Americans feel less and less connected, even lonely at times. A 2010 AARP survey found that 35 percent of adults older than 45 are chronically lonely. This stands in stark contrast to 20 percent of a similar group measured a decade earlier. And guess who Samuels’ top clients are? You guessed it: middle-aged men, the same people found to be more chronically lonely today than before, in times when the Internet was less widespread.

But my burning question is: in the midst of this loneliness, are we desperate enough to actually resort to paying a complete stranger to snuggle with us? After all, don’t we have friends to do that with? Lovers? Our mothers? If not, Samuels may be onto something.

Okay, I know what you’re thinking. Since the dawn of mankind and man’s first rejection, humans have always been lonely. What’s to say that the Internet has anything to do with it? But if Americans swapped even part of those 32.7 hours a week they spend plastered in front of a computer screen for some serious snuggling action with loved ones, perhaps Samuels would have less clients. One could only speculate. According to the Snuggery, “Though science has unquestionably supported the psychological and physical benefits of non-sexual touch, Americans distinctly lack it.” Why is that? Are we as a nation culturally arid when it comes to the human touch, and if so, are these habits technologically-rooted?

I would argue that they are. But I will let MIT Professor and psychologist Sherry Turkle speak for me:

“We live in a technological universe in which we are always communicating. And yet we have sacrificed conversation for mere connection. E-mail, Twitter, Facebook, all of these have their places — in politics, commerce, romance and friendship. But no matter how valuable, they do not substitute for conversation.”

The psychologist argues that technology has gotten us used to being “alone together.” “We want to customize our lives. We want to move in and out of where we are because the thing we value most is control over where we focus our attention. We have gotten used to the idea of being in a tribe of one, loyal to our own party,” she claims.

She further states that “texting and e-mail and posting let us present the self we want to be,” giving us the freedom to edit as we wish how we present ourselves to the outside world. A hefty claim, particularly since, wrought with texting or not, humans can decieve face-to-face or via old-fashioned letters, too. Nonetheless, her statement that through technology “we have learned the habit of cleaning [human relationships] up” leaves me wondering if Samuels is feeding a sickness, the need to divulge to another ourselves as we are, which Truckle claims modern society lacks.

And while others will argue that those who are social online tend to be social offline, the research cited in support of this claim, a Pew study on social networking sites, doesn’t really make the cut in convincing me. Why? Because on the premise that Facebook users have closer relationships, the study was not done in comparison to those that spend less time online, but to general internet users. In other words, the variable was not internet usage, but site choice.

But I digress. To end on a paradoxical note, one reader responded to Turkle’s op-editorial with a glaringly ironic observation: “Isn’t it ironic that the most-fowarded [sic] story is an article that describes how relationships now consist of nothing more than forwarding articles to each other!”