What happens when you give a group of hackers and artists access to 3D printers and free reign in the Metropolitan Museum of Art for a weekend? According to MakerBot Industries co-founder and CEO Bre Pettis, nothing short of amazing. “We’re showing the world what kind of awesomeness we can create!”

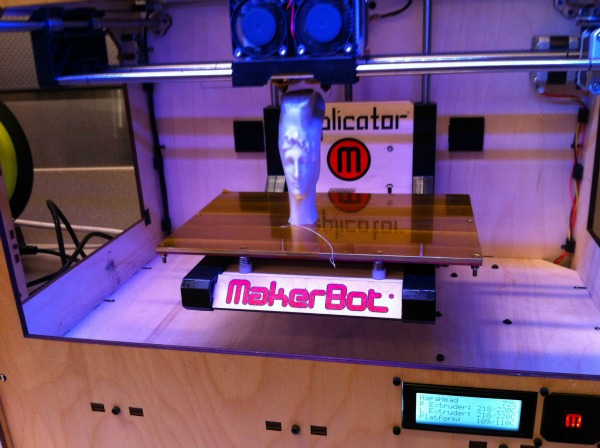

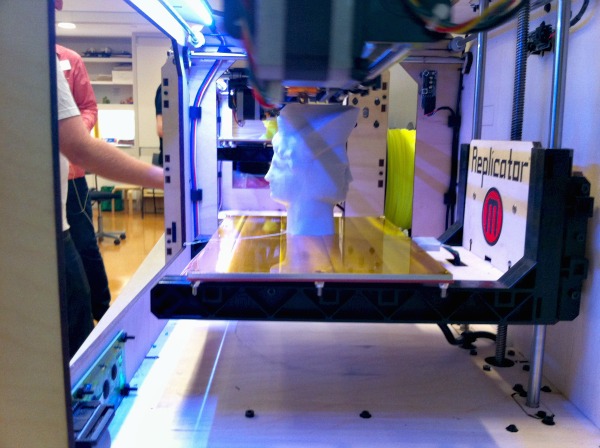

Earlier this month, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City hosted Pettis and an exclusive group of artists as they selected works from the historic museum collection to mashup using Autodesk’s 123D Catch and MakerBot’s Replicator. 123D Catch is software that helps designers create models out of existing physical objects by converting digital photographs into realistic digital representations using cloud based photo stitching technology.

Here’s how it works:

The artists turned hackers, including Chicago-based Tom Burtonwood, and New York-based artists Micah Ganske and Colette Robbins, manipulated the models and used MakerBot Replicators to print small 3D models of their artistic visions.

Colette Robbins’ piece (pictured above) was inspired by art in the Met’s collection as well as her own work that includes large graphite paintings of monolithic double-headed structures that reference the temples in Angkor. For this project, she was really inspired by the Southeast Asian wing of the museum, as well as the double-headed Roman god Janus. Janus has two heads facing opposite ways, one past and one present.

“I decided to use that concept of heads facing opposite ways to fuse head of a pre-Angkor structure and a sculpture of the face of Paris (the greek mythological character who is credited with causing the Trojan War)” notes Robbins. “I like the idea of fusing two culture together since there are so many cultures represented here at the Met.” Robbins noted that she also narrowed the model to reference Swiis sculptor Alberto Giacometti who is famous for his elongated figures.

MakerBot’s Pettis (pictured above) chose to make a miniature version of the museum by creating a model of a museum guard, a bench, and an iconic flower vase. He took a break from this hard work on day two of the hackathon to explain his motivation for the event with infectious enthusiasm.

“We’re remixing art. These scuptures aren’t under copyright because they are old, so you can use your MakerBot to do anything you want with them. For example, you can apply an algorithm to make them blocky, or you can rearrange the limbs of the sculpture to put them on backwards.”

The partnership with the Met started because the museum was interested in 3D printing. Members of the Met team visited the MakerBot Botcave (the official name for the company’s Brooklyn headquarters) and they got really excited about what they saw.

The admiration was mutual. Pettis, who was at one time an art teacher in the Seattle Public Schools, always wanted to have unmitigated access to a museum collection. “I thought that it would have to be a heist!” he laughed. “But the team at the Met was like, no this is cool, we want to make the museum collection as big as the Internet!”

Pettis was referencing Thingiverse, MakerBot’s digital community that serves as a wikipedia of objects. All objects that are uploaded to the community can be downloaded and redesigned. Users can also print any object that they see on Thingiverse using a MakerBot Replicator. By uploading models of museum sculptures to Thingiverse, the collection then can become available to anyone who wants to print the smaller 3D models. This can help students learn about sculpture in an interactive setting. It’s more meaningful that studying sculptures in a 2D art book.

“Autodesk’s 123D Catch combined with MakerBot can really going to help further education here at the Met because if you go around the museum, you can see that everyone has their camera out. They are all interacting with some sort of technology to filter their experience. Encouraging groups to make their own sculptures from the collection at the Met could be something that the museum could do to help people learn about art.” notes Robbins.

Unlike most competitive hackathons that celebrate developer rockstars in a small but insular community, the MakerBot hackathon was welcoming and noncompetitive. No one was going to get a check in the mail for hacking on an API. Instead, Pettis stressed that “anyone can do what we’re doing. We’re just taking digital photos of art and using tools that are available to anyone to create new and interesting things. The software is free, but you need a camera (you can use your phone’s camera) and you can come in and acquire art.”